This is part 2 of a 2 part post. The first part can be found here

In part 1 we looked at Attribute-based access control, how it’s superior to roles-based access control and then did a shallow dive in to the authorisation framework that we use at Polylytics.

Policy Management

In part 1 of this post I discussed how several of our clients use the core authorisation framework in isolation and then it’s been the job of the developers to implement IPolicy<TUser, TEnvironment> using code. Whilst this works well for the smaller clients, we also want to be able to manage policies at runtime where necessary i.e. update the policies without compiling any code.

So, how do we implement IPolicy<TUser, TEnvironment> using a UI at runtime?

Enter the DSL

You’ll remember that one of the methods in the IPolicy interface is GenerateFilterAsync. This returns an Expression<Func<TResource, bool>>, so we somehow need the UI to generate expression trees for us. Not only that, but the two other methods in the interface could simply make use of that expression tree to execute themselves. You’ll also remember that Wikipedia says:

…the concept of policies that express a complex Boolean rule set that can evaluate many different attributes.

So, given all these requirements, it makes sense for us to provide a really flexible UX that allows complex boolean evaluations but also generates expression trees, and that means implementing a DSL.

As you can imagine this DSL ends up looking an awful lot like a C# lambda expression (with a few more English words thrown in). For example,

@resource.GrandParent = @user.Grandparent

and @environment.Location = "Home"

and @action = "SendPresent"

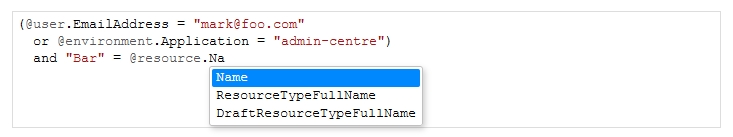

Now, this clearly isn’t overly friendly for non-developer types but given a few examples it’s fairly easy to conjure up new policies. The big win for us though, is that not only do we have this DSL but we’ve also implemented an editor that has autocompletion, styling and (fairly) sensible error messages when the user gets something wrong. Here’s what it looks like:

This editor is provided through a web-based UI hosted inside the admin application itself (but kept separate) and the authorisation that enables you to access the editor is driven by a policy of the authorisation framework that you can edit inside the editor: dog-fooding indeed!

How does it all work?

The DSL Parser

The first step to building the policies is the parsing of the DSL and the generation, from that DSL, of an expression tree. To perform all this work we’ve used Antlr which is “a powerful parser generator for reading, processing, executing or translating structured text or binary files”.

In essence, it allows you to define a “grammar” for your DSL and then it will generate a parser for you which will then allow you to visit the parse tree that it generates.

Once we have this parse tree it’s then simply a matter of mapping from the parse tree over to an expression tree. I say “simply” - there’s some intracacy in here as the policies appear to be dynamically typed but we’re generating a strongly-typed expression tree.

The policy builder

Now that we have our expression tree we must implement IPolicy<TUser, TEnvironment>. This is the job of the policy builder. We could have simply just used the expression tree as is, compiled it and then executed it with the given parameters.

However, in this framework we’ve also introduced the concept of “meta resources” and these have the signature:

public interface IMetaResource { }

public interface IMetaResource<TReferenceType> : IMetaResource {

Expression<Func<TReferenceType>> ReferenceExpression { get; }

}

These interfaces can be implemented by multiple classes so that you can write a single policy against a group of related classes. For example, you might want to write a single policy for all your reference data so you mark them with IReferenceData (which extends IMetaResource) and then you can write a policy against IReferenceData instead of each individual class. The generic interface takes this one step further and allows you to reference the properties of a “super” class (the TReferenceType) as if they’re properties on the resource itself.

As a result, the policy builder needs to know the concrete types at runtime and implement the functions for the IPolicy then.

You’ll also notice that when we call GenerateFilterAsync we are returned an Expression<Func<TResource, bool>> but our DSL parser has generated an Expression<Func<TResource, TAction, TUser, TEnvironment, bool>>. So, the final job of the policy builder is to apply the known values for TAction, TUser and TEnvironment to the expression tree so that we can return an expression tree only in TResource. This “Application Expression Visitor” is actually cleverer still in that it evaluates the expression tree as it goes, reducing it where possible so that the only terms left are those that reference TResource or, as is sometimes the case, the true or false constant expressions. For example, if the action parameter is equal to “bar” then we can reduce this expression

(resource, action, user, environment) => resource.X == Y && action == "foo"

to this:

(resource) => false;

And then we know it’s pointless handing this over to be executed by our ORM and we can just return the empty set for that resource, user and environment.

The editor

The editor is build on top of CodeMirror which is an excellent javascript based code editor.

In our case we simply provide a function to generate suggestions for the auto-completion based on the classes that we know we want to authorise.

Other than that, it’s all down to CodeMirror!

Wrap Up

That’s the end of our introduction to the ABAC authorisation framework that we use at Polylytics. I hope to be able to open source the code at some point in the near future…